Meet our food and beverage partners for this year’s Simply diVine, as they answer four of our burning questions.

We look fourward to seeing you on Saturday, April 27, at Hollywood Forever!

Purchase your tickets today at simplydivinela.org. Use code CAMPUS19 to receive $25 off FOODIE tickets.

Located in the Silver Lake neighborhood, The Black Cat is a gastropub that has deep roots to the LGBT civil rights movement. What occurred at the historic establishment in 1967—a precursor to the Stonewall Riots in New York by two years—is a testament that LA’s LGBT community was ahead of its time and deserves international recognition.

LGBT News Now: Some of our readers may not realize this, but The Black Cat is a vital component of L.A.’s LGBT movement. Please educate the neophytes.

Lindsay Kennedy, The Black Cat Co-Partner: If only President Obama, in his 2013 inaugural address to the country, had referenced The Black Cat in the same sentence as The Stonewall Inn, then perhaps the name and the history of The Black Cat would be more familiar. I’m no historian so I don’t pretend to be an expert on the subject matter, but my partners and I (and everyone who works at The Black Cat) believe we have a moral obligation to be able to speak intelligently about The Black Cat’s role in the local, as well as the national, LGBT rights movement. So here goes:

There is a plaque on the wall outside The Black Cat that reads:

The Black Cat

Site of the first documented LGBT civil rights demonstration in the nation

Held on February 11, 1967

Declared 2008 Historic Cultural Monument No. 939

Cultural Heritage Commission City of Los Angeles

This plaque commemorates the peaceful demonstrations that followed from a night of violent police raids that took place on New Year’s Eve 1967 at The Black Cat and other gay bars in the Silver Lake neighborhood. Before the clock struck midnight, about a dozen undercover plain-clothed cops positioned themselves inside The Black Cat. As the New Year rang in, the patrons celebrated with embraces and kisses, and the police began making arrests. Raids of this nature where not uncommon but, in this instance, the police initially refused to show their badges, which created a lot of confusion and misunderstanding. In the panic that ensued, violence erupted and the police began beating both customers and employees of The Black Cat who in turn fought back against what they perceived to be a gang attack or something of a similar nature. When it was all over, two cops were injured, and fourteen patrons—as well as two employees of The Black Cat—were dragged outside and arrested on the sidewalk. The bulk of the charges levied were for lewd conduct related to same sex kissing. Eventually six men were tried and found guilty of lewd conduct, a conviction that required them to register as sex offenders. Trials and convictions like these were not uncommon; what was uncommon this time was the grounds on which these men and their attorneys mounted their defense. Rather than deny that they were gay or that they were kissing (which was the norm), they argued for the first time ever that they had the right to be gay and to kiss and that they should be afforded the same rights under the Constitution of the United States that straight people were afforded: equal protection, equal rights. This was a watershed moment that wove gay rights in to the broader fabric of human rights and what it meant to be an American.

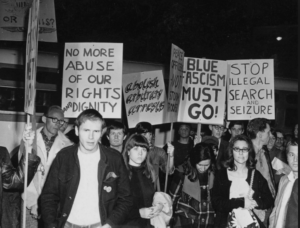

In the weeks that followed the police raids, there was a groundswell of people ready to claim their Constitutional rights. Alexei Romanoff, perhaps the sole surviving organizer of the Black Cat Protest, estimates that several hundred people showed up on February 11, 1967. These brave men and women who stood on the corner of Sunset Blvd. and Hyperion Ave. on February 11, 1967, to peacefully protest the injustices inflicted upon the patrons and staff members of The Black Cat Tavern the previous New Year’s Eve did so almost two years prior to the Stonewall Riots in Greenwich Village New York, the designated birthplace of the modern gay rights movement.

In the weeks that followed the police raids, there was a groundswell of people ready to claim their Constitutional rights. Alexei Romanoff, perhaps the sole surviving organizer of the Black Cat Protest, estimates that several hundred people showed up on February 11, 1967. These brave men and women who stood on the corner of Sunset Blvd. and Hyperion Ave. on February 11, 1967, to peacefully protest the injustices inflicted upon the patrons and staff members of The Black Cat Tavern the previous New Year’s Eve did so almost two years prior to the Stonewall Riots in Greenwich Village New York, the designated birthplace of the modern gay rights movement.

LGBT: Has the Silver Lake neighborhood truly changed since The Black Cat’s heydays?

LK: If by ‘heydays’ you mean 1966/1967, then, yes, Silver Lake today is vastly different than the Silver Lake of the 1960s. Fifty plus years ago Silver Lake was a middle-class Latino community. It was also a burgeoning hotbed of counter-cultural activity, anti-war sentiment, and resistance. When The Black Cat opened 53 years ago, it was one of a handful of clandestine bars within walking distance of Sunset Junction that catered to a gay subculture that had been developing in the area since the early ‘60s. In a time when being gay was considered a crime, The Black Cat existed beneath the surface, underground, and largely out of sight. It was by necessity a secret to all but a few. By design it was in the shadows with a nondescript facade and ambiguous street signage. The street-facing windows were blacked out to help protect the anonymity of the patrons inside. To be seen at The Black Cat by anyone other than a fellow patron was a genuine peril to one’s existence in daily life. The threat of being outed came with serious social as well as legal consequences, and as the police raids on New Year’s Eve proved, it was dangerous to be gay. The demonstration in February 1967 is remarkable for many reasons. First and foremost, it was the first documented gay rights demonstration in America. It was also a peaceful, well organized, law abiding protest against police brutality that for the first time wrapped gay rights into a broader national fight for civil rights. But what I’m most struck by is the bravery of the men and women of different races, some but not all of whom were gay, who showed themselves to the public, to their parents, to their children, and to their co-workers in support of the people who were beaten and arrested on suspicion of being gay. The protestors stood up knowing that, for their actions, they would suffer a range of consequences from discrimination at best, criminalization at worst. This is something that Alexei Romanoff, an LGBT rights activist and possibly the sole surviving organizer of the protest, is quick to point out. The iconic black and white press photographs taken outside The Black Cat during the protest (which hang on the walls inside The Black Cat today) tell a story of both defiance and deference. Next time you look at those images, take in their faces. Notice that no one is smiling. The protesters’ expressions reveal their visceral fear of retribution, but yet they stand tall. There’s a certain caught-in-the-spotlight quality to the people in the images that I find frightening, endearing, and very genuine.

So yeah…I think Silver Lake is a much different place now than it was in 1966 (insert cliche hipster joke here). That said I want to emphasize different without qualifying it with better or worse. I’m a straight white male who rode into Silver Lake on a horse named Gentrification. Some would say that disqualifies me from speaking about what Silver Lake used to be, and I agree. People like Alexei Romanoff, David Farah, and Wes Joe are way more qualified to speak about that. But, as a bar and restaurant owner, I meet a lot of people at The Black Cat, some of which have lived in this neighborhood for many years and some who are new on the block. There’s a lot of creative energy here. There’s still a spirit of engagement in social and political issues. There is a respect for the past. My partners and I are committed to being responsible caretakers of the historical narrative that gives our bar and restaurant its namesake and to supporting organizations such as the Los Angeles LGBT Center. And say what you want about gentrification, but a building doesn’t become a Cultural-Historic landmark without a commitment from multiple stakeholders; namely the landlord and many dedicated community stakeholders. In a town notorious for paving paradise and putting up a parking lot, we are proud to chaperone this chapter of The Black Cat and give people a tangible piece of history to remember it by.

LGBT: The Los Angeles LGBT Center is celebrating its 50th anniversary. What do you predict will happen to the LGBT community in the next 50 years?

LK: Respectfully, I don’t think I’m in a position to make any predictions about the next 50 years in the LGBT community, or otherwise! All I can say is that as long as we’re fortunate enough to be the caretakers of this chapter of The Black Cat, we will do our part to raise awareness about LGBT issues by providing people with a tangible piece of human rights history.

LGBT: If we could order just one cocktail and one dish at The Black Cat, what should they be?

LGBT: If we could order just one cocktail and one dish at The Black Cat, what should they be?

LK: Thanks to Ben Schwartz, who runs our bar program, our cocktail list changes several times a year. Tonight, if I have to pick a drink for you, I’d go with an Abeja Reina (Queen Bee): mezcal, lemon, and honey served on the rocks with a chili lime salt rim. This cocktail is a Ben Schwartz original that showcases his approach to cocktails: spirit forward and perfectly balanced.

Our menu also changes throughout the year. Chef Trevor Rocco puts his own twist on classic American tavern fare, and it’s always ingredient driven, bold flavored, and beautiful. But again, if you can only order one dish, it should be a burger with raclette cheese, melted onions, shredded lettuce, house made sweet & tangy pickles, and fries. I would also add avocado and bacon…but that’s just me.